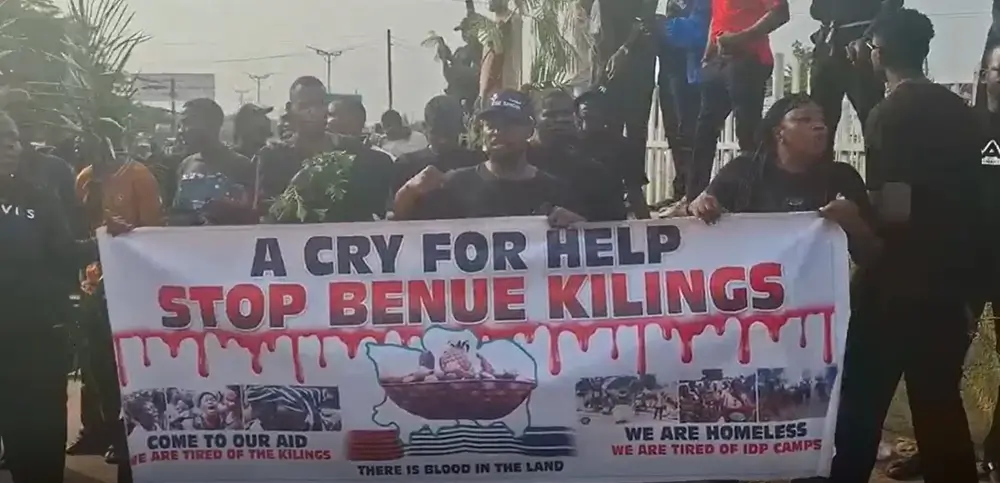

Massacre and Displacement in Benue (June 13–14, 2025)

Between June 13 and 14, 2025, armed herders launched a coordinated assault on Yelewata, a village in Guma Local Government Area of Benue State, central Nigeria. Witnesses report that the attackers employed sophisticated firearms and petrol to raze homes and market stalls, leaving more than 200 civilians dead, including children, women, and internally displaced persons taking refuge in the community’s storage facilities [1] [2]. Amnesty International and on‑the‑ground humanitarians later confirmed that many victims were burned alive in their houses, with charred bodies discovered in what had been a bustling market [3] [4].

The violence forced an estimated 6,500 people from their homes, overwhelming both informal host families and newly established camps. Some 3,000 displaced persons have been relocated to a newly constructed camp at the Ultra-Modern Market in Makurdi, the state capital, while others remain scattered across neighboring communities [1]. The destruction of food stores, wells, and family shelters has precipitated acute shortages of emergency shelter, potable water, and basic foodstuffs. Local civil‑society groups report that overcrowding and inadequate sanitation in temporary sites have heightened the risk of waterborne disease outbreaks and malnutrition among children [5].

In response, Governor Hyacinth Alia declared Benue “under siege” and called for a reinforced military presence to protect vulnerable rural communities, though critics argue that past deployments have failed to deter repeat attacks [6] [7]. International agencies, including UNICEF and the International Committee of the Red Cross, are mobilizing emergency relief—distributing tarpaulins, hygiene kits, and ready‑to‑eat meals—while appealing for additional funding to address both immediate lifesaving needs and longer‑term reconstruction of homes and markets [5]. The incident underscores the deepening herder–farmer crisis in Nigeria, where competition over grazing routes and farmland continues to fuel one of the Sahel’s most intractable intercommunal conflicts [8].

The Psychological Angle

Mind Engrave, through established theories and research, examined the Benue massacre and its aftermath. This further illuminate the deep wounds inflicted on the whole communities, especially on the children, when violence and displacement shatter daily life.

Collective Trauma and Grief

When an entire village is attacked, the violence transcends individual suffering and becomes a shared wound. Sociologist Kai Erikson first coined “collective trauma” to describe how catastrophic events damage the social fabric itself. In Yelewata, the burning of homes, markets and food stores not only destroyed physical structures but also annihilated the routines and rituals around which communal identity was woven. Market days, harvest festivals, and intergenerational gatherings, all markers of belonging, are now tainted by memories of carnage. As people mourn hundreds of lost neighbors, they experience grief not only for individuals, but also for the way of life that has been irrevocably transformed.

Grief in such contexts is often “complicated,” characterized by relentless rumination, aggressive anger, and persistent yearning for lost security. Rather than a linear process of “closure,” survivors may cycle through shock, disbelief, and numbness alongside recurrent panic and hypervigilance. Public memorials, or the absence of them, play a crucial role in collective healing. In Benue, where resources for formal remembrance are scarce, informal rituals (shared meals, storytelling circles) may provide vital outlets for communal mourning and help restore links of mutual support.

Disruption of Social Cohesion and Communal Identity

Social cohesion depends on trust, reciprocity, and shared cultural symbols. Armed aggression aimed at civilians deliberately targets these bonds, fracturing relations not only between attackers and victims but often among survivor groups themselves. Competition for scarce resources, such as shelter in host homes, food aid, can strain the very networks that would otherwise offer protection. Over time, such distrust can calcify into social fragmentation, making coordinated relief efforts more difficult and prolonging existential anxiety.

Communal identity is rebuilt when survivors renew collective meaning: joint decisions about rebuilding, shared responsibility for protecting the displaced, and inclusive rituals that acknowledge both loss and resilience. Psychologically informed interventions, such as community dialogues or participatory reconstruction projects, can foster empowerment, giving survivors a sense of agency over their future rather than leaving them passive recipients of aid.

Children’s Resilience and Risk

Children comprise a disproportionately vulnerable subgroup in mass displacement. Neuro-developmental research shows that exposure to violence during critical windows of brain maturation heightens risk for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, and attentional problems. Displacement uproots children’s sense of safety and disrupts foundational attachment bonds. When parents themselves are traumatized, grappling with grief, depression or survivor guilt, their capacity for sensitive caregiving may be compromised, leaving children without the reliable “secure base” that underpins healthy emotional regulation.

Yet children also possess remarkable plasticity and potential for recovery. Protective factors include consistent routines, opportunities for play and education, and the visible support of caring adults. Programs that restore schooling, even in makeshift shelters, can reintroduce normalcy, re-establish peer connections, and scaffold cognitive and social development. Peer‐led activities, art therapy, and culturally congruent storytelling can help children process loss, rebuild hope, and strengthen group identity among displaced youth.

Attachment, Development, and Vulnerability to PTSD

Attachment theory emphasizes that children look to caregivers for cues about the safety of their environment. In Yelewata’s camp in Makurdi, overcrowded tents and competition for water or food can overwhelm families’ coping capacities. When a parent’s own stress becomes dysregulated, marked by irritability, withdrawal or emotional numbing, the child’s internal working model (“the world is safe,” “I am loved”) can be shattered. Longitudinal studies indicate that early disruption in secure attachment correlates with poorer stress tolerance and higher PTSD rates later in life.

Interventions grounded in attachment repair, such as trauma‐focused parental guidance or multi-family support groups, can mitigate these risks. Teaching caregivers simple, everyday practices (eye contact, responsive play, predictable mealtimes) reinforces children’s emerging sense of trust and mastery. Even small successes, such as learning to draw again, forming a new friendship, can catalyze a virtuous cycle of confidence and engagement.

Toward Healing: Psychosocial and Policy Implications

A transformative, empathetic response must operate on multiple levels:

- Individual and Family Support: Rapid deployment of trained community health workers to deliver psychological first aid; establishment of “safe spaces” for children with structured activities; parenting workshops focused on stress management and nurturing techniques.

- Community‐Level Interventions: Facilitate local remembrance ceremonies; support community‐led reconstruction projects; create forums for dialogue between displaced persons and host communities to rebuild trust and prevent social fragmentation.

- Policy and Coordination: Advocate for protection of civilian areas under international humanitarian law; ensure that displaced families receive reliable access to shelter, clean water, and education; coordinate mental‐health services within broader relief operations to integrate psychosocial care from the outset.

By addressing both the immediate emotional wounds and the longer‐term disruption of social cohesion, interventions can help Yelewata’s survivors, especially its children, reclaim agency, restore communal bonds, and pave a pathway toward collective recovery. In doing so, they honor not only the memory of those lost, but also the enduring human capacity for resilience and renewal.

Odusanya Adedeji

Odusanya Adedeji A., is a Licensed & Certified Clinical Psychologist whose domain of expertise cuts across management of specific mental health issues such as, Depression, PTSD, Anxiety & Anxiety related disorders, substance use disorder, etc